What is an Asiatic composite bow?

It is the most sophisticated and technologically advanced type

of bow, being made entirely of natural materials like wood, horn,

sinew, and hide or fish glues. These type of bows have been developed

in multiple styles all over Asia and were in use until slowly

replaced by firearms. Several of these bows are still being made

by professionals today.

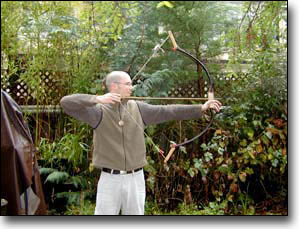

This is the first bow of this type I have made and it was more of a learning process than anything else. I was able to make a bow that shoots and did not break, but it was a far cry from a masterpiece.

After having made a number of selfbows and sinew backed recurves, this king of bows was always in the back of my mind. Over the years, I collected materials and read articles and books on the subject and it seemed harder and harder to actually make one. Then suddenly, while my lovely wife was on a trip to India, the time was right.

I did not replicate a certain bow or any specific style of bow, but opted to make a bow that would be on the safe side, that would not break or warp and be reliable to use.

This article will be on the work process only and not on composite bows in general.

Getting started:

The Horn Strips

The length and width of the bow were pretty much determined

by the pieces of horn I could cut from the gemsbok horns (Africa)

that I had ordered.

The horn was split down the center into two halves with a hacksaw,

while being held in a vise. The solid tips and the somewhat thin

and frizzy ends were cut off, so that I ended up with two pieces,

19 inches long. Then the rippled outside was worked smooth with

a coarse file and the inside was shaved down with a homemade tool

held at a 90 degree angle, in order to achieve an even thickness

of ca. 3/16 inch.

This was many hours of work already, but now the fun starts.

Bending those pieces into nice flat strips that actually end up

looking like store bought pieces of fiberglass. What an amazing

transformation!!!

By boiling the horn and clamping it down flat, it will stay in

that shape once cooled. I used a big square aluminum foil dish

and put it over two flames on our kitchen gas stove. In my case,

the horn is being clamped between two solid flat surfaces like

a block of wood and a metal strip.

If you put your C-clamps right on the horn, you will get some

deep dents. Now place the whole assembly under boiling water with

only the C-clamps sticking out so you can gradually tighten them

while the horn softens. I boiled the hell out of the horn and

it was not damaged! Refill your pan with hot water when necessary

. It took a while of fiddling with those clamps while steam was

fogging up my glasses. I burned my fingers on the hot pan and

almost got boiling water on my feet. Imagine the workshops back

then, where they were working on batches of 500 bows at a time.

Once I got those pieces 90% flat, I took a knife or file and filed

them into nice rectangular strips. I then shaved the horn strips

to their final thickness of 2/16 inches. The final dimensions

were: 19 inches long, 2/16 inches thick, and tapering from 1 inch

to 1 5/8 inches wide

Hey, look at those two neat strips!!!.

The Wood Core

I used rock maple for the core. Moreover, as with a piece of wood for bow making, the grain should run straight. I did cut it with a table saw into a rectangular strip of 2/16-inch thickness. That's it!!

The Handle

The handle will be glued to the back of the bow and not to

the belly as with self-bows.

Some bows have an extreme reset in the handle, but I settled on

ca. 20 degrees because more reset would stress the limb-handle

connection more and make the bow unstable.

The question of how thick, how wide and how long of a handle to

make takes some playing with those variables. I tend to make them

fairly chunky because weight in the handle does not slow down

the arrow. I feel it adds weight to the bow where it is permissible

and so adds stability (any comments?).

I make bows symmetrical, meaning no long and no short limb and

I shoot from the center just holding the bow lower in the handle.

Why? I don't know. The handle ended up to be ca. 6 1/2 inches

long, 1 1/8 inches wide and 1 1/2 inches deep. I steamed the wooden

core and clamped it to the handle. After it cooled and dried,

I glued the pieces together with epoxy.

Gluing Horn to Core

Epoxy sounded like one more safety feature. I did not have

the nerve to play with fish glue!

I made the horn reach ca. 1 inch into the handle and filled the

space between the two horn strips with a piece of sheet brass.

Again to add weight to the bow. I used metal straps as support

for an even gluing and 8 clamps on each limb. After that, cut

the excess wood to match the horn. At this point, I used rawhide

to bind the handle-core-horn connection, as this area will undergo

a lot of stress.

The Ears

Spruce is recommended for its lightness and stiffness, so I

opted for 6 inches long ears coming of at an angle of 45 degrees.

I made them out of two parts, to leave the limbs as long as possible

and to get an extra glue line. Next time, I will use a less complicated

way of making them. However, at this point I did not want any

part to break off or separate when I string that bow up.

The grain ran nice and parallel with the ears and they ended up

being just under 1 inch thick and tapering from 1 inch to 1/2

inch at the tips. I also bound that ear limb connection with rawhide

strips.

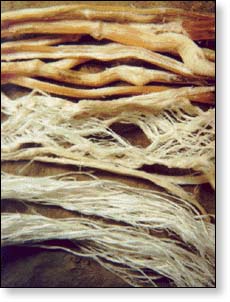

Sinewing

I used roughly 8 deer backstraps and 7 leg tendons. I sinewed

the bow the same way I would sinew any other bow. Two layers were

put down. Then I waited 7 days and put on another two layers.

My hide glue was rabbit skin glue from the art store. Before putting

down the sinew, I pulled the bow into more of a reflex and secured

it with a string between the tips. In addition, I bound the handle

and ear areas some more to hold down the sinew. I took a 4 week

break while everything was drying!

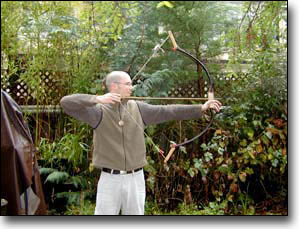

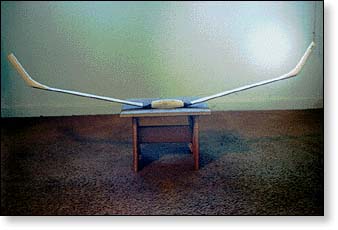

After removing the string between the tips, the bow measured 18

inches of reflex between handle and ears. On one side of the handle,

an air bubble had developed between sinew and wood core. The sinew

probably pulled up while shrinking, even with it being bound down.

After some debating of what to do, I did not touch it at all and

oddly enough, the bubble seemed to have disappeared.

The misalignment of the limbs that occurred and seemed to come

out of the handle area might have something to do with that flaw,

but unfortunately, I did not mark if it was left or right of the

handle. So my advice is, always mark the areas where some irregularities

appear, so that you might learn something if that area later ends

up being a weak spot.

The Covering

I did not sand the sinew smooth but covered both limbs with thin homemade goat rawhide that I had dyed brown with black walnut husks. I slightly soaked the hide and then just laid it on, overlapping onto the horn. No binding was necessary. The handle area is covered with a dehaired road kill squirrel skin (finally, I found some use for that tiny hide).

The Bridges

They were made of two oval pieces of thick leather each. I soaked the parts in hide glue and then clamped them together to dry. This makes a nice hard fileable leather. I concaved one side to receive the string and the other side was ground to fit the knee of the ears. Elmers glue held them in place. They are 1 1/8 by 1 13/16 and 1/2 inch thick more than I needed actually.

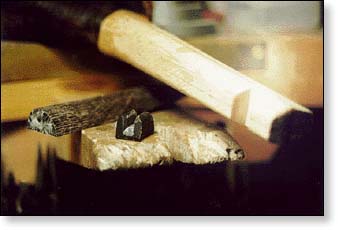

The Nocks

For the string nocks, I cut a square section out of the ears, a little less than half way through and glued in a piece of horn with a groove just deep and wide enough to hold the string. This is another area that receives a lot of stress. Cutting the nocks any deeper was somewhat scary.

The whole bow got three coatings of homemade varnish, made from finely ground pine pitch dissolved in alcohol. It looked great and had a wilderness smell.

And now, I'm finally done!!!

Nevertheless, the worst part is stringing that thing. I had tremendous respect for the weapon I created after I had read how powerful these tools can be and what a procedure it was to string them.

Stringing the Bow

So far, I have not spent much time on the bowstring. I replicated

a Korean bowstring made out of separate pieces for the loops,

tied onto the main string. But the knots for tying seem to stretch

out, so I will have to wait for some advice from the pros.

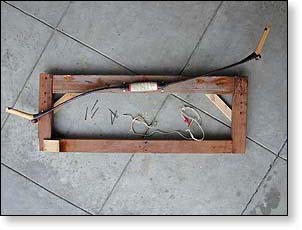

I nailed together a crude stringing jig, put the bow on it, got

all breakable things out of the way, locked the dog up, put on

full body armor, and strung the thing up. I gradually pulled it

over a couple of days. Everything was fine, no cracking, no nothing.

BUT! The limbs are not perfectly aligned and the bow only draws

about 40 pounds at 32 inches. (I have no problems with finger

pinch with the bow being 55 inches measured along the belly) Therefore,

it seems to be a fairly slow shooter. In addition, the reflex

came down from 18 to 10 inches after a while. How those guys get

the tips to touch is still a mystery to me.

Heat Treating

To align a composite bow, it needs to be heated and clamped into the desired shape. Taking horn off the belly is the last thing you want to do. So, what I tried was a localized heat box. Meaning, I put a piece of wood and C-clamp in place (limb seemed to come off at a wrong angle from the handle) and encased the whole area with cardboard and tape. I left an opening for a hair dryer. Also, the top of the C-clamp was sticking out. While the heat inside build up, I gradually tightened the clamp. After a cooling down period overnight, I restrung the bow and it looked pretty good. However, after a day of shooting, the problem came back. I need help from the pros!!!

All in all, this bow is a beautiful piece of work and I marvel at the combination of materials, each doing its share and fitting into the whole. Nature at its finest, once more showing me again that everything is connected and all things work together as one.

With this, I will leave it.

My thanks to the three volumes of the Bowyer's Bible and Tim

Baker for his telephone counseling.

Check out these web sites for more infomation on composite bows:

- www.student.utwente.nl/~sagi/artikel/

- www.atarn.org

E-mail your comments to "Markus Klek" at markusklek@yahoo.com.

Markus Klek resides in Germany.

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013