Pottery is the miracle of turning raw earth into sophisticated vessels. Pottery-making was not universal in the Californias. Boiling with hot stones in a container of animal skin, a tightly woven basket, or a pecked and ground stone bowl was the lot of most. Except for some archaic clay boiling stones, figurines and crude crockery, a well-developed ceramic tradition only arrived in California from the east during the last one thousand years. A. Kroeber and Malcolm Rogers suggested that an early Puebloan-style pottery entered east-central California from Nevada. It became the ware found historically among the Mono and Yokuts. Another independent style that employed a paddle and anvil had likely evolved in central Mexico, spread to western Mexico and southern Arizona, and flourished among people of the Yuman stock, principally along the Colorado River where they practiced limited agriculture. From there, the style passed to other Yuman bands in the deserts and mountains and to their Shoshonean-speaking neighbors of southern California: the Chemehuevi, Serrano, Cahuilla, Cupeño and Luiseño. This was not the tediously painted pottery of collectors' boutiques and pictured in eye-dazzling coffee-table books. It was the practical ware of people who hunted and gathered from the land and needed strong pots for cooking, bowls for eating, and large ollas to store seeds and water. Rogers noted that for thinness and hardness, the best prehistoric Yuman wares exceeded the famous Puebloan pottery of Arizona and New Mexico and in certain areas even equaled it in per capita production. Mexican California used this ware extensively. Many shards have been found at places such as the Sepulveda adobe hacienda near Newport Bay. Though not overdecorated, the soft functional curves of the vessels and the mysterious fire-clouding of the brown-red surfaces were beauty enough.

When Rogers conducted a study of Yuman ceramics in the late 1920s, the craft had already gone into decline. He found purity of technique best preserved among the Southern Diegueño (Kumeyaay) at Manzanita in San Diego County. The tradition was mainly in the hands of one potter, Rosa Lopez (Owas Hilmawa), whose procedures he recorded, supplementing his monograph where appropriate with archaeological and ethnographic data and the memories and practices of other potters of Yuman stock. Rosa Lopez died in 1930 and many would say that today, on the brink of the twenty-first century, Yuman pottery is also dead. But in Lower California, in the mountain village of Santa Catarina and in the surrounding rancherias, the pottery lives much as Rogers described it at Manzanita more than sixty years ago. During Rogers' time, only women engaged in pottery-making. That is true of the Santa Catarina area today. Paipai Josefina Ochurte still sits in the sun and coils her pots on a summer's day as her ancestors did for countless generations. Some of the other local potters also have Paipai blood but learned their craft from Southern Diegueño Kuatl mothers and grandmothers and speak both Paipai and Kuatl Yuman dialects. Some belong directly to the Southern Diegueño (Kumeyaay) Kuatl lineage.

In rendering Rogers' account of the process of making a Yuman food bowl with a recurved rim (one of an eight-piece batch made by Rosa Lopez), I will add significant information from Michelsen's notes taken in the 1960s, a study by Gena Van Camp in the 1970s, observations by Michael Wilken in the 1980s, and experiences of my own in the 1990s. Rogers wrote, for example, that clay pipes were no longer made by the Southern Diegueño in the 1920s but their construction was still understood. He described them as always bowed, with a flat triangular projection on the outer side of the arch and midway between the ends that served as a handle, A small hole through the handle allowed for the insertion of a carrying thong. These pipes were still made at Santa Catarina in the 1990s. I have watched them being made and have smoked native tobacco in them. For convenience, the process of Yuman paddle and anvil ceramics can be broken into ten stages, beginning, of course, with finding the clay itself.

Kamia seed jar at left in Rogers, 1936. To the right of seed jar are Mohave motif: bowl with rain pattern, ladle painted in fish backbone design and stylized cottonwood leaves on bowl from Kroeber; 1925.

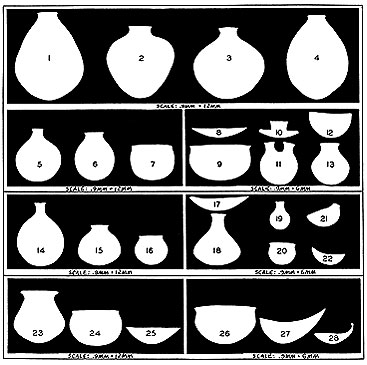

Yuman- style pottery followed natural shapes, suggested Gena Van Camp, in particular the gourd. Bottles were gourd-like; a few, asymmetrical (21) like certain gourds; others bilobate as are gourds; the scoop was but a gourd cut in half; and pottery rattles were like the gourd ones. Other pieces took the shape of the baskets which preceded them (8). Forms, of course, were always functional: the bottoms if pots rounded, for example, so they could be carried in a net or placed in sand or balanced on three rocks if the hearth; the necks of water ollas were constricted to prevent spillage and evaporation.

Forms were not random in distribution. Semi-globular food bowls (26), plate-like parching trays (17) and ladles (28) stood out among the agricultural Colorado River Yuman groups while the desert Kamia favored graceful, long-necked water ollas (14). The slender water olla neck was often only an inch in diameter on the inside; they came in many sizes; small ones 19), sometimes with a thong strung from two holes just below the rim, were used as portable canteens. Kamia food storage ollas, on the other hand, were infrequent and not often of great size. In contrast, large storage vessels (1-4) typified the seed gathering mountain groups to the west.

Southern Diegueño (Kumeyaay) storage ollas, with a maximum height around 33" and capacity of 27 gallons, no two exactly the same shape, were filled with seeds or other dry food or even cordage, sandals, ceremonial paraphernalia or anything else that would not spoil and was not for immediate use, and cached in caves, among rocks or buried near villages. A flat ceramic lid, small bowl, a lump of unfired clay or wad of grass sealed the top. Pitch or unfired clay held the pottery lids to the ollas. Some ollas were made with guttered or collared necks likely to provide a seating for a bowl lid. Large ollas were important vessels and meant to last. A pitch plug or cemented potsherd patched holes; infrequently, fresh clay was applied and the area refired. Mesquite or elephant-tree gum mended a crack; or cracks were repaired by means of adjacent drilled holes, with cordage or rawhide thongs to lash the sides together.

Buried to its mouth and the mouth left open, an olla became a trap fir small animals. All groups used medium-sized jars at home or in temporary camps to hold food or water for immediate use. The Kumeyaay water olla (5) averaged 17" in height. Canteens (11) sometimes had multiple necks, two, three, or even four. A grass stopper secured the contents. Cooking bowls varied in size, some as small as cups. Earlier forms were straight-sided (12), later developing recurved rims (7). Shallow bowls were often painted and used for serving food, winnowing or parching seeds, as scoops and dippers or as lids for olIas. Cooking pots (6) were about twice the height of the cooking bowl and had a smaller mouth.

Yumas (Quechan) made "mixing" bowls (26), parchers (25) and boat-shaped ladles (27), sometimes with a small cylindrical handle from the rim or a tab-shaped handle at a right angle to the rim (28). The handles of such ladles occasionally were molded with curved parrot-shaped noses and coffee-bean eyes -- "quail heads" as the Mohave called them. Yuma water-storage ollas (23) were Piman in profile and flare of the rim. Older ollas had smaller openings and rounder bodies; one for young girls who were not adept at carrying them on their heads was still more slender-necked and small-mouthed. Yuma food-storage ollas also had somewhat smallish mouths. A potsherd ground to disk shape was pitched over the mouth to seal the contents for a long storage.

The rare floating bowl -- a shallow bowl over 3' wide in which women placed perishables and babies -- was pushed ahead of a swimmer to cross a river; very few could make such a large piece.

Cooking bowls (24), squat, wide-mouthed with recurved rims, were given a special protective finish by the Colorado River tribes and desert Kamia. A stucco of coarse sand or crushed rock, or coarsely crushed potsherds, added to clay mixed with water was plastered over the outside of the bowl after it had been sundried and before firing. They applied the slip and tamped it down with the palm of the hand, thickest on the base -- up to 1/4 " -- tapered on the sides and discontinued a few inches below the rim. It was said it kept the inner wall of the bowl from cracking. As pieces of stucco came off through use, fresh patches were applied.

The Mohave made a special temper for the cooking ware clay itself of a course white sandstone, easily crumbled; they added two parts of this to three parts of clay. They sunfired the cooking pot for two days, applied stucco and fired it an entire night in a pit kiln. (Mohave ware not intended for cooking had a potsherd temper and were fired one at a time on the surface of the ground; they were placed upside down on three burnt pieces of clay and the fuel stacked in a cone around the pot.)

In the end, function followed need: the Kumeyaay and Paipai, Michelsen discovered, may have made a vessel for one purpose but readily used it for another -- a cooking pot could store seeds, a seed-storage olla could hold water -- practicality governed the small band, hunter-gatherer mind-set.

I. Gathering Clay

Rogers divided the combined area of southern California and Lower California into a desert region, where mainly sedimentary but some residual clays resulted in a buff-colored ware, and a mountain area with only residual clay that yielded a reddish-brown pottery. Residual clays accumulated from weathering and decomposition of granite outcroppings in the southern California batholith, the underlying rock of mountains extending south from the transverse ranges of Orange County to the tip of Baja. These clays built up in pockets or layers near springs and along streams, both old and recent, They came complete with their own temper, particles of quartz, feldspar, and mica (which was of two kinds: biotite and muscovite). The mica could often be seen shining on the surface of the pottery made from this clay. Generally brown, impurities of iron compounds or carbonaceous material or more complete oxidation gave the fired clay a dark, reddish color. Van Camp found that shards made from residual clays were thicker than those of sedimentary clays.

Sedimentary clays (whose fired pots went from buffs, pinks and light reds to lavenders and grays) developed from fine particles of soil carried along and separated out from coarser particles by water that then deposited them on the banks of the Colorado River, in ancient desert lakes and over other alluvial areas of the Colorado desert. To avert cracking, coarse tempering material had to be added to this clay before firing. Salts were often found in sedimentary clays and would form a scum on the surface of the fired pot or cause a vessel to crack. To prevent this, the potter would actually taste the clay. Those with high salt contents were avoided, especially for a cooking pot.

Women from the Manzanita area often traveled into Northern Diegueño territory to obtain a highly micaceous clay to make cooking pots. Their local clay, widespread in the region on the sides of canyons and valleys, was a coarse decomposed granite that seemed an unlikely raw material for ceramics, but it was much used. By weight, 85 percent of the substance was quartz, mica and partially altered feldspar crystals. Before modern tools, quarrying was with jagged rocks and sharpened sticks. The Southern Diegueño and Paipai of the Santa Catarina region still dug clay with an ironwood digging stick in Michelsen's time (Michelsen and Smith, 1972).

Michelsen noted that Petra Higuera, an elderly Kuatl woman of Santa Catarina, unlike many other local potters, would travel as far as 20 miles to procure clay having less coarse foreign matter. The result was superior pottery. Some obtain clay today in Santa Catarina almost at their doorstep from the valley floor near the local stream.

The Mohave dug sedimentary clay from the Colorado River bank at the base of Parker Mesa, a clay found nearly everywhere along margins of the broader areas of the Colorado River valley, according to Rogers.

Except in cases of special necessity, clay was gathered and pottery made only during the summer months when fuel and ground were driest. As one moves south, summer in effect begins earlier. In the mountain desert of Santa Catarina, potters are at work by springtime, rising early in the morning and working throughout the day directly in the sun so the pot will dry rapidly and the finished piece can be placed in the kiln. Wilken described Santa Catarina and the quarrying of local clay, recognized in finished vessels by its many flecks of shimmering mica:

At dawn on a clear spring day, an Indian woman sets off across the desert to a place where her grandmother taught her to gather clay, followed by an assortment of children, grandchildren, and dogs. She walks along a well-worn trail through manzanita, yucca, and juniper bushes. Making her way up the low hill at the base of Red Rock Mountain, she comes to a clearing and begins to dig into the dark red veins of earth, looking for clods with just enough sand and not too many rocks (Wilken, 1987).

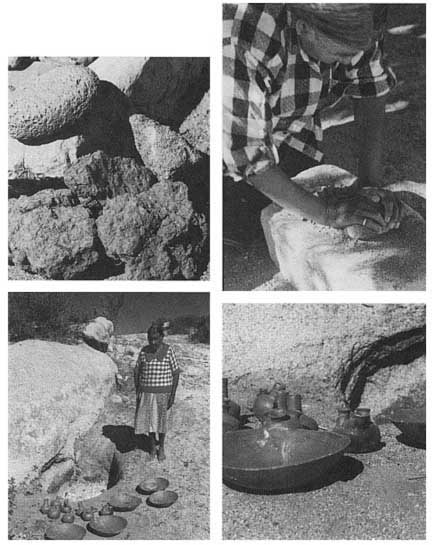

The miracle of pottery: Josefina Ochurte turns unbroken

clods of earth into finished household ware. Mano and clods, above

left. Pulverizing with mano on the grinding stone, above right.

Below, she stands by the pit kiln and recently fired canteens

and winnowing bowls.

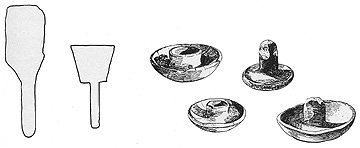

Old-style Southern Diegueño paddle on left, new on right. (Drawn from Rogers, 1936.) Next, two pottery anvils of the Cocopa in the University of California collections. At right, early Southern Diegueño pottery anvils from Campo, California, Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation: (First Diegueño anvil, about 9 cm. in diameter.) These are virtually identical with those made by Josefina Ochurte in Santa Catarina in 1994 (drawings in Gifford, 1928).

The article is from the book, entitled "Survival Skills of Native California" (ISBN 0-87905-921-4), by Paul Douglas Campbell. Permission to use the article on the PrimitiveWays website was given by Mr. Campbell. Paul Campbell can be contacted through his publisher, Gibbs Smith, P.O. Box 667, Layton, Utah 84041.

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013