After the plants were cut and stripped, offerings were made before spinning

the fibers began. Prayers such as this one were also said.

Significance in Hawaiian Culture -- So important was the olona plant to the early Hawaiians, that it was grown in small plantations and was the only endemic species and the only non-food plant grown in that manner. This is certainly evidence of its great value to the natives, but it is only part of the story. In a society without nails or man-made fibers, olona fibers had many, many important uses in the Hawaiian culture. The white cordage derived from the fibers was highly valued for its lightweight and exceeding great strength under duress. Therefore it was also often used for bartering in the Hawaiian community.

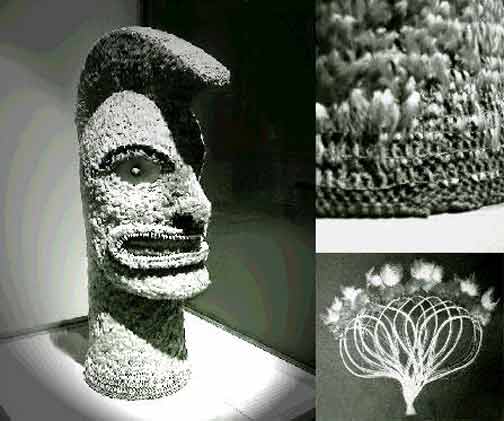

Taxes were paid to the King after the fall harvest during the Makahiki, and the monarchy received many of these payments in the form of olona. The ali'i, or royalty, had many uses for this valuable commodity, including its use in the making of the royal kahili (a cylindrical plume of feathers on tall poles associated with the ali'i), feathered images of the Hawaiian gods, and for the fabrication of the royal cloaks, capes and helmets.

Still further evidence of the value of olona developed after contact was made with sailors from the Western world. Sailing ships traded for miles of rigging made from olona, considered to be better in every way than conventional rigging, which was twice the diameter. This, in turn, was important to the Hawaiians because it afforded them bargaining power with the sailors to trade the olona for things newly arrived from the outside world - things which the Hawaiians strongly desired to possess.

Growing Environment -- Handy and Handy (1972) reported that olona grows in "boggy interior valleys" and "upland areas", and Kamakau (1976) described olona habitat as rainy, marshy, mossy, in mountainous areas, often near banana trees. Although it is not common today, this rain forest shrub can still be found on all six major islands in the gullies of lower elevation forests, near the 2,000-foot level, and near streams.

Although olona still grew in wild clumps, the Hawaiians grew it in patches and, if space allowed, in large plantations of up to two acres. Stalks were encouraged to grow straight and tall and close to one another to reduce branching. Lateral branches were regularly removed from upright stems to reduce the number of holes in the fiber. In a year to eighteen months the plants were mature enough to harvest. They were 6 to 10 feet tall, and the bark could be easily stripped at this young age

Identification -- Olona, Touchardia latifolia, is a wood shrub endemic to Hawaii. Though it is a member of the Urticaceae, stinging nettle family, olona is free of stinging hairs. The plant is characterized by its prominent stipules, which are two to three inches long. The leaves are large, 9 to 16 inches long and 5 to 9 inches wide, ovate in shape with serrated (fine-toothed) margins, three distinct veins, and green on both sides. Male flowers are borne in dense clusters, 1/2 to 1 inch in diameter and 3 to 5 inches long. Female flowers are borne on smaller heads in shorter clusters. The fruit is roundish and mulberry-like, and at maturity it is bright to dull orange and is fleshy.

Preparation -- The processing sheds were normally constructed near running water, since water was used in the process of extracting the fibers from the mature olona stems. The bark was first carefully stripped and hung to drain in the shed. After draining, the strips were laid in the running water for a day or two.

Next the strips were placed on a narrow board, fastened securely at the top of the board, and then scraped with a tool called the uhi, made from the backbone of a turtle or a segment of its shell. After drying and after the removal of the outside bark, the resulting product was a mass of fine white fibers, which were then dried in the sun. At the same time workers were separating the clean strong fibers into various widths, and bundling them into rolls for the return to the village.

There they were bleached in the sunlight and later twisted by the village women into fine cordage of varying thicknesses.

Finished Products -- In Hawaii Nei, olona was the main fiber used for aho, fishing line, where the no-kink and no-stretch factors were very useful. Fishnets with large mesh, upena, as well as finer fishnets, and net bags for carrying containers, koko, were also crafted from olona fiber. To prolong its life, it was often treated with kukui oil.

An ancient net maker bartered dogs, loads of fish, and food from his field and taro lo'i in exchange for 4,000 or more strands of olona fiber, which his wife would braid into cord for the net. A fine-mesh net for catching small fish might take a year to complete. The size of the cord increased when larger four and five-finger nets were made for catching big fish such as ulua and papio.

Carefully crafted olona fibers also made up the net base that provided backing for the exceptionally fine feather cloaks, ahu'ula, as well as for some of the feather helmets, mahiole, and for ti leaf capes, ahu la'i. Kahili feather standards were wound with olona cord, and olona cordage was superior for tying adz heads to hau wood handles.

Other uses for olona in ancient Hawaii were as threads for stitching together kapa, tapa bark cloth, into garments, for stringing and wrapping all manner of lei, to tie off the umbilical cord after a birth, for canoe lines, stretching drum skins over drums, and for every possible purpose that we today might use rope, twine, string or thread.

Olona cordage has been replaced by nylon and other synthetics of modern technology, but its incredible strength has not lessened by comparison. Olona could still be used in communities or cultures that produce their own cordage, for it is superior to hemp and agave. The strands are also rather soft and one can imagine their use in clothing. Olona has been forgotten, however, except in places remote from modern society where it is still cultivated on a small scale.

E-mail your comments to "Gerry Labiste" at a.graphics@verizon.net

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013