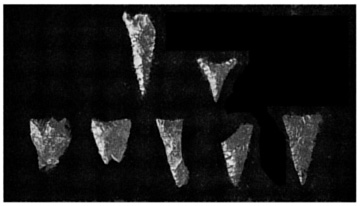

Hypothetical manufacturing sequence for Cottonwood triangular projectile point from initial blank (on far left), which had been chipped from a core, to completed point (on far right). these examples are taken from actual lost or discarded points (probably because of undesirable shape or breakage -- note missing corners or tips) from an archaeological workshop site in Afton Canyon California (Schneider 1989). The Cottonwood style of very simple arrowhead began around A.D. 1000 and continued in use to historic times. Most of those found at Afton Canyon were of local jasper or chalcedony. The Eastgate example (with broken barb, above left), according to some researchers, preceded Cottonwood point in the archaeological record (A.D. 700-1300). "Cottonwood point" may even have been a stage in the production of Eastgate until, through simplification, they gradually became the end product itself. The small point above right is probably a rejuvenated Cottonwood point that had been broken during use.

B. B. Redding's Account

A nineteenth-century description by B. B. Redding preserves in simple words and rich circumstantiality the purpose of flint knapping. Step by step we experience a California Wintun Indian flaking an arrowhead.

He brought, tied up in a deer skin, a piece of obsidian weighing about a pound, a fragment of a deer horn split from a prong lengthwise, about 4 inches in length and 1/2 an inch in diameter, and ground off squarely at the ends -- this left each end a semicircle, besides two deer prongs (Cariacus columbianus) with the points ground down into the shape of a square sharp-pointed file, one of these being much smaller than the other. He had also some pieces of iron wire tied to wooden handles and ground into the same shapes. These, he explained, he used in preference to the deer prongs, since white men came to the country, because they were harder and did not require sharpening so frequently . . . . Holding the piece of obsidian in the hollow of the left hand, he place between the first and second fingers of the same hand the split piece of deer horn first described, the straight edge of the split deer horn resting against about one-fourth of an inch of the edge of the obsidian -- this being about the thickness of the flake he desired to split off; then with a small round water-worn stone which he had selected, weighing perhaps a pound, he with his right hand struck the other end of the split deer horn a sharp blow. The first attempt resulted in failure. A flake was split off but the blow also shattered the flake at the same time into small fragments. He then repeated the operation, apparently holding the split deer horn more carefully and firmly against the large piece of obsidian. the next blow was successful. A perfect flake was obtained showing the conchoidal fracture peculiar to obsidian . . . . the shape naturally taken by the obsidian when split off in this manner is that of a spearhead, and it could be put to use, for this purpose, with but slight alteration. the thickness of the flake to be split off depends upon the nearness or distance from the edge of the obsidian on which the straight edge of the split deer horn is held at the time the blow is struck.

He now squatted on the ground, sitting on his left foot, his right leg extended in a position often assumed by tailors at work. He then placed in the palm of his left hand a piece of thick well-tanned buckskin, evidently made from the skin of the neck of the deer. It was thick but soft and pliable. On this he laid the flake of obsidian, which he firmly in its place by the first three fingers of the same hand. He then rested the elbow on the left knee, which gave the left arm and hand holding the flake, firm and steady support. he then took in his right hand the larger of the two deer prongs, which, as has been stated, had its point sharpened in the form of a square file, and holding it as an engraver of wood holds his cutting instrument, he commenced reducing one edge of the circular form of the flake to a straight line. With the thumb of the right hand resting on the edge of the left palm as a fulcrum, the point of the deer prong would be made to rest on about 1/8 of an inch or less of the edge of the flake, then with a firm downward pressure of the point, a conchoidal fragment would be broken out almost always of the size desired. The point of the deer prong would then be advanced a short distance and the same operation repeated, until a few minutes the flake was reduced to a straight line on one edge. As this operation broke all the chips from the under side of the flake, if left in this condition the arrowhead would be unequally proportioned, that is, the two cutting edges would not be in the center. He therefore with the side of the deer horn, firmly rubbed back and forth the straight edge he had made on the flake until the sharp edge had been broken and worn down. The flake was now turned end for end in the palm of his hand and the chipping renewed. When completed an equal amount was taken from each side of the edge of the flake and the cutting edge was left in the center. It was now plain that the straight edge thus made was to be one side of the long isosceles triangle, the form of the arrowheads which is used by his tribe.

With the flake of obsidian firmly held in the cushion of the left palm and the point of deer horn strongly pressed on the edge of the flake, the effect was the same as the blow which split the flake from the larger piece. While, however, he was not always sure of the effect of the blow in splitting off the larger flakes out of which to make the arrowheads, he in not instance appeared to fail in breaking out with the point of deer-prong the exact piece desired. The soft thick pliable piece of tanned deer skin on which the flake in his left palm was held, may have added to the cushion, but seemed to serve no other purpose than to save his hand from being cut by the countless sharp chips as they were broken off. One of the long sides of the arrowhead having been thus formed, the flake was turned over and the other side formed in the same manner. As, however, very much more of the obsidian had to be chipped away, he brought more pressure upon the point and broke out larger chips until the flake began to assume the shape desired, when the same care was exercised as when the first straight edge was made. In breaking out large or small chips the process was always the same. The pressure of the point of deer horn on the upper edge of the flake never appeared to break out a piece, which, on the upper side, reached beyond where the point rested, while on the under side the chip broken out might leave a space of twice the distance. Invariably when a line of these chips had been broken out the sharp edge was rubbed down, the flake turned end for end and the chipping renewed on the other side. By this process the cutting edges of the arrowhead were kept in the same line. The base was formed in the same manner . . . .

The chipping out of . . . . (the side notches) . . . . was the last operation to be performed. It seemed to me more difficult than any other part of the work, and I thought that in this would be the danger of the loss of all the patient labor that had been expended. In practical operation it was the simplest, safest and most rapid of all his work. He now held the point of the well-shaped arrowhead between the thumb and first finger of his left hand with the edge of the arrowhead upwards, the base resting edgewise on the deer-skin cushion in the palm. He then used the smaller deer prong, which had been sharpened in the same form as the larger one, but all its proportions, in every respect, were very much smaller; its point could not have been larger than on sixteenth of an inch square. He rested this point on the edge of the arrowhead where he desired to make the slot, and commenced sawing back and forth with a rocking motion, the fine chips flew from each side, the point of the deer horn descended, and in less than a minute the slot was cut. The arrowhead was turned over and the same operation repeated on the other edge. It seemed that by this process, if he desired, the arrowhead could have been cut in two in a very few minutes. He now examined his work in the strong sunlight and, being satisfied, handed me the completed arrowhead. It had taken him forty minutes to split the two flakes from the large piece of obsidian and chip one of them into the arrowhead. A younger man, equally expert, would probably have done the work in half an hour.

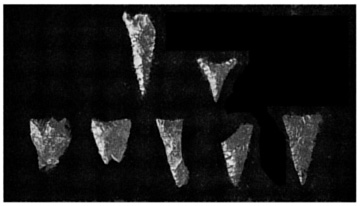

California arrowheads. Top row: from foothills of southern Cascades near Oroville (including Yahi territory), before A.D. 1000. Point on left is desert side-notched style. Bottom row: arrow points from coastal southern California and offshore islands, from A.D. 500 until European contact (All of these and many other stone artifacts are found in Joseph and Kerry Chartkoff's "the Archaeology of California, 1984.)

The article is from the book, entitled "Survival Skills of Native California" (ISBN 0-87905-921-4), by Paul Douglas Campbell. Permission to use the article on the PrimitiveWays website was given by Mr. Campbell. Paul Campbell can be contacted through his publisher, Gibbs Smith, P.O. Box 667, Layton, Utah 84041.

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013