Seeds ripen but once a year, and often in abundance. This makes them one of the food resources suitable for storage along with meat and tubers. Seeds have an additional advantage in that they are designed to be dormant for long periods of time, so are less work to prepare. Meat, fish, berries, tubers and bulbs all require extensive work to dry before they can be stored. Meat and fish are thin sliced and hung, berries and cooked roots are smashed into flat "fruit and root leather".

California Native Peoples stored many different kinds of seeds, but are best known for storing acorns. In many parts of the state, this was the main source for plant calories. In the southern deserts, pine nuts and mesquite beans supplemented or took the place of acorns, and were stored in similar granaries. Smaller seeds were stored in tight baskets hung inside the houses, as were acorns in areas where they were a smaller part of the diet. Separate silos from the great Central Valley, the mountains of the north and east, and parts of the desert south are illustrated here.

Storage requires overcoming several factors: moisture (mold, mildew and bacteria); rodents; and birds. Strategies vary according to climate, with rodents being a big factor in the desert, and moisture a bigger factor in the rainy north. Rodents and insects were dealt with by constructing or lining the granary with tough and/or bitter, aromatic plants which either mask the smell of the food, or repel pests from eating through. The structure itself kept birds at bay. Moisture then became the remaining design issue. Moisture comes from the ground, so most granaries were elevated or had a moisture barrier such as a stone below them. It can also come from the sky, so granaries in rainy areas were thatched or otherwise well roofed. And it can also come from the air as fog, so granaries might be located where prevailing breezes minimized this threat.

The species of acorn stored also factors into storage options. Most species of oak were used, but they vary in nutrition, moisture content and texture. Tan oak and black oak both have large acorns, with significant tannins (insect repellent), low moisture, good nutrition and good quality flour when pounded. These were the preferred species where they grew. Live oak are the highest in protein, low in moisture and otherwise good, but are more inconsistent in annual abundance, and smaller in size. Valley oak is lowest in nutrition and highest in moisture of the commonly eaten acorns, and required the most effort to dry. Unlike others, these acorns had to be shelled first, and there are pictures of them being threaded onto strings and hung up to adequately dry. Gold cup oak was avoided, as it produced poor quality flour.

Harvest was done so as to avoid wormy acorns. The early drop contained most of these, so the ground beneath the tree was cleaned and the men and older boys climbed the tree with poles and knocked down the good acorns. Once harvested, all acorns need to be dried before storage. This was typically done by spreading them out in the sun on bare ground or rock. During this phase, protection from raiding birds and squirrels was a critical factor. I envision a prominent role here for young boys with simple weapons defending the family food and hoping to score a little protein. A change in color and feel tells you when they are dry. (For those drying acorns today a note of caution - drying with heat causes the acorns to turn dark and become unusable.)

Now the fun begins, as the acorns must be carried from the oak groves back to the village site and stored away where they can be protected. One museum carrying basket was filled with acorns and weighed in at around 100 lbs. Families in the Sierra Nevada foothills are thought to have eaten around five hundred pounds of acorns per family member per year. So a family of five would need over a ton. Once at the village, they were either stored in granaries, or inside the house. I have found pictures and descriptions of four styles of these outdoor structures, each suited to its environment.

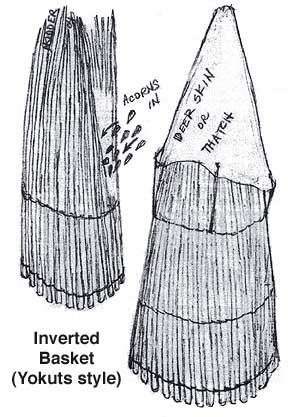

The Inverted Basket

Use of this variation is illustrated in a movie using Yokuts

Indians from the Bakersfield area of the Central Valley. Frank

Latta, a local historian set up a typical village scene for this

educational film made around 1960. To construct one, straight

willow shoots about 1 inch in diameter are stuck into the ground

in a circle. They are twined together at the bottom and about

1/3 of the way up, then filled to the twining (presumably with

a layer of rock separating the nuts from ground moisture) Another

row of twining is followed by more acorns, then the shoots are

tied together at the top to make a pointed cone, and this sealed

with thatch or deer hide. Acorns could be removed from this model

by pulling the upright apart.

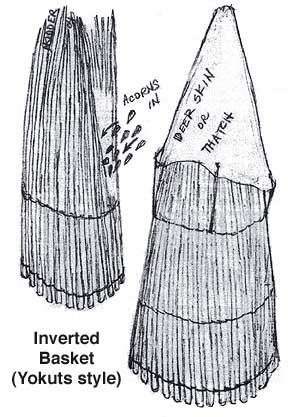

The Desert "Birdnest"

Throughout the deserts of southern California and adjacent

states, the typical storage structure is a platform or large boulder

with a coiled globular basket made with very thick sidewalls of

tough or bitter material such as willow. Miniature examples of

these are made for sale by the Kumeyaay Indians of the San Diego/Mexico

border area. Their walls are of whole shoot willow (complete with

leaves), and an inch or so thick with a relatively small opening

and fitted lid. Others are more open on top, to be covered with

mats or bark if it should rain. Protection from rodents may have

been provided again by the hunters of the village.

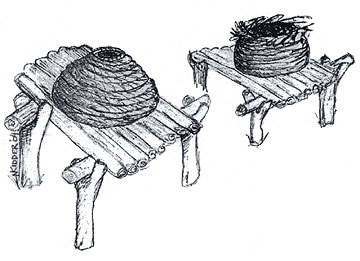

The Hanging Basket

There are drawings of storage baskets hung in trees, or supported

by poles rather than inside the house. This seems to be a simple

extension of indoor storage. If hung outside, a basket must be

well thatched to keep off the rain.

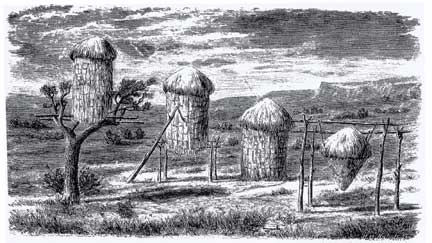

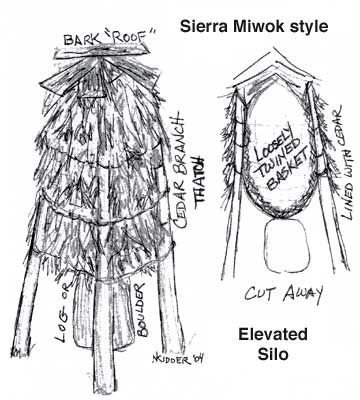

The Elevated Silo

This type was common in the Sierra Nevada foothills. It is similar

to the hanging basket, but the inner basket is much rougher, and

is not separate as a basket. The upright posts go in first, then

a large rock or log to support the bottom. Then branches are twined

or woven together more loosely than a basket, then lined with

sticks and leaves to keep the acorns from falling through, and

often providing natural insect repellent by using cedar, mugwort,

sage or other strongly aromatic plants. When filled, the open

top was roofed with slabs of bark from redwood or other trees.

REFERENCES:

Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8 - California, Robert F. Heizer (Editor, 1978), Smithsonian Institution,

Washington D.C.

Handbook of the Yokuts Indians by Frank F. Latta (1949), Kern County Museum, Bakersfield, CA

Survival Skills of Native California by Paul D. Campbell (1999), Gibbs Smith Publishing, Salt Lake City

Temalpakh, Cahuilla Indian Knowledge and Usage of Plants by Lowell Bean and Katherine Siva Saubel (1972), Malke Museum Press, Morongo Indian Reservation

Tribes of California by Steven Powers (1976), University of California Press, Berkeley, CA (Reprinted from Dept. of the Interior publication dated 1877)

This article was first published in The

Bulletin of Primitive Technology (Fall 2004, #28)

E-mail your comments to "Norm Kidder" at atlat1@aol.com

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2017