INTRODUCTION

The Waorani has been the last indigenous groups living in the Ecuadorian Rain Forest (South America) to be contacted by the modern world. Being so, they still preserve a great amount of their traditional knowledge and customs.

In the old days, every Wao (and the majority of the Amazon native people) used to sleep in hammocks. Every night they collected the fire embers and spread them under their hammocks to keep them warm at night. Even with tropical weather, the territory where they live is a little bit cold at night. It is still rain forest, but high over the sea level, near where the forest and the Andes meet. It also makes up for the lowering of the body temperature as metabolism decrease when sleeping.

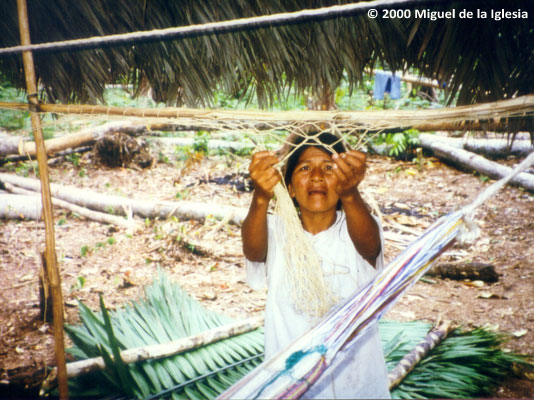

The weaving of the hammocks has been traditionally a women's job among the Waorani. This technique has been passed from mothers to daughters for thousands of years. Young girls learn the skill from their mothers, aunts or grandmothers.

Waorani mother and daughter working together to extract the fiber from Opogenkowe palm (Astrocaryum chambira) leaves.

Nowadays, due to the great influence of missionaries and many other foreigners (Cowori, in Waorani language), a lot of Waorani are abandoning their customs and traditions. Some of them sleep on very simple beds made out of some wood planks put together over the ground by a couple of logs lied down (just an imitation of western beds, and in fact, far less comfortable than hammocks). But there are a number of Waorani that still prefer to sleep in traditional hammocks, and, of course, Waorani women still remember how to traditionally weave them.

Waorani woman weaving a hammock.

Nowadays traditional hammocks are also made to sell them to the tourists. Unfortunately, the amount of money they get for them is very small in comparison to the work and time invested in making them.

The aim of this article is to show how the Waorani women weave their hammocks step by step.

PREPARING THE MATERIALS

Cordage

First thing a Wao woman does when she wants to make a hammock is to gather and prepare all the necessary materials. For the particular case of the hammock, she needs a lot of cord, approximately 1 kilometer (3,281 feet). This cord is made with the fiber from the leaves of a plant they call Opogenkowe (Astrocaryum chambira).

Each leaf of the Opogenkowe palm (Astrocaryum chambira) yields two pieces of fiber. The part used is the “skin” of the young leaves.

This fiber is gathered all through the year by women and men. Every time they are hunting, fishing or gathering fruit and vegetables, and they come across a good Opogenkowe plant, they take the leaves home for the women to make into cordage.

Opogenkowe fiber can be dyed, and these women are masters at it. With the bark of just one species of plant, they can get a great variety of colors. But they do not use just one species. They know a lot of plants from which they can use the bark, the roots, or the leaves to dye with. By using all these different colors together, they make really beautiful items, not only hammocks, but also bags, fishing nets, necklaces, etc.

The fiber is twisted into cord using the "leg (thigh) rolling method". The technique is described by Norm Kidder in his article Making Cordage By Hand (Bulletin of Primitive Technology #12, Fall, 1996, Figures 6a-c). Once they have a very long piece of cord, they make a ball with it and store it until needed.

Opogenkowe does not grow wild in Europe nor in North America, but other species can be used, like raffia (Raphia sp.), dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum), or even cotton (Gossypium sp.).

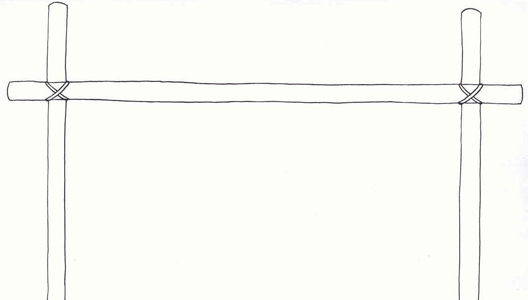

The Frame

Once a woman has all the fiber she needs, she looks for three long, thin pieces of wood. They have to be straight and about 5 centimeters (2 inches) in diameter. These three poles are used to make a frame like the one shown in Figure 1. This frame must be driven into the ground, so it stands. The width of this frame will determine the later length of the hammock, whilst the width of the hammock will be determined by the amount of cordage used to weave it. That is, the number of times the cordage will go around the frame. It is advisable to make the hammock wide enough, as the wider it is, the more comfortable, and more people can use it at the same time.

Figure 1: The wood frame.

WEAVING THE HAMMOCK

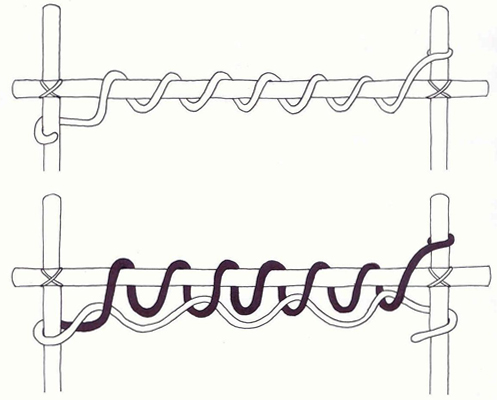

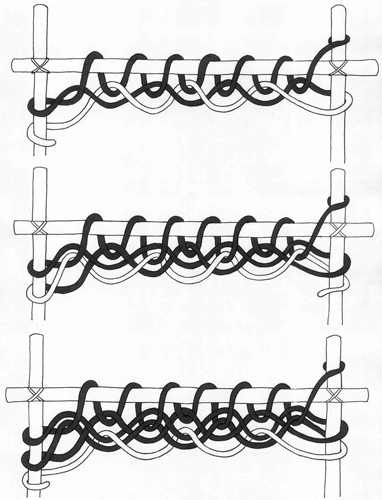

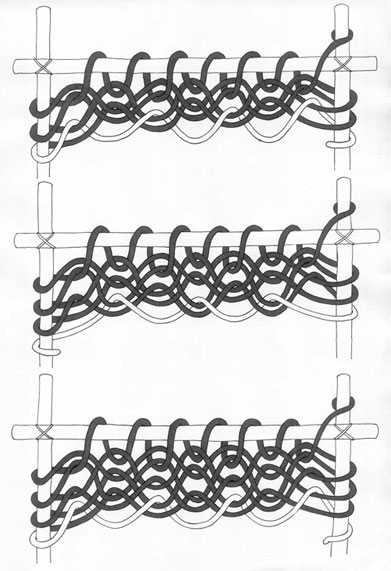

The first step is to tie one end of the cord to one of the vertical poles above the level of the horizontal pole. They make the cord go around the horizontal pole several times, and then behind the opposite vertical pole and around. The more times they go around the horizontal pole the tighter the weaving of the hammock will be. Next, they go on weaving following the pattern shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4. The net woven this way, will constitute the main part of the hammock. They weave it until they estimate it is big enough.

Figure 2: First steps in the weaving of the hammock.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Successive steps in weaving the hammock.

They twine the fiber into cord while they are weaving. When the first ball of cordage comes to an end, they simply stop and continue thigh rolling more cordage at the end of the previous one. This way, they avoid making any knots that would make the hammock somewhat uncomfortable. If you are using already twined fiber, at this point you can just tie the beginning of a new ball of cordage to the end of the previous one using a fisherman's knot or a sheet bend knot. Just make sure to make it coincide with one of the sides of the wood frame, instead of making it in the middle of the hammock.

Once the hammock is big enough, they simply tie the end of the cord to the side of the net. Then they untie the other end of the cord (the one tied to the vertical pole of the frame at the start), pull from it so the first part of the weaving doesn't stay loose, and then tie it to the side of the net too.

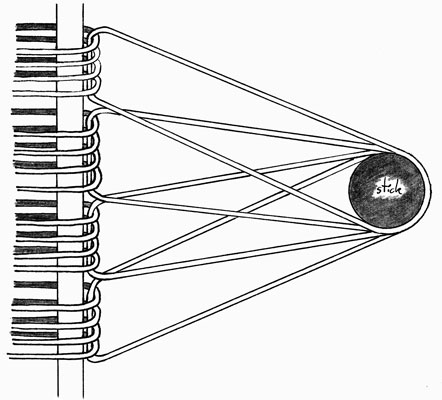

The last thing to do is to slide the ropes that will be used to set up the hammock through the laces on the two ends of the net (the ones that went around the vertical poles before). They use Opogenkowe cord for this too. The easiest way to do it is to take the frame out of the ground and lay it flat on the floor. Then drive a stick into the ground at a certain distance from one of the sides of the frame. This distance will determine the length of the hanging section of the hammock. The cord is passed through the first 4 or 5 lateral loops that formed at the vertical poles while weaving. Then it goes around the nearby stick. Now it goes through the next 4 or 5 loops of the hammock and around the stick again. This has to be repeated until the cord goes through the last loops of the hammock (Figure 5). It is important that the cord going through the loops in the central area stays a little longer, so, when hung, the hammock won't lay flat, but with a nice "canoe" shape.

Figure 5: Scheme of how to add the cord that will be used to hang the hammock.

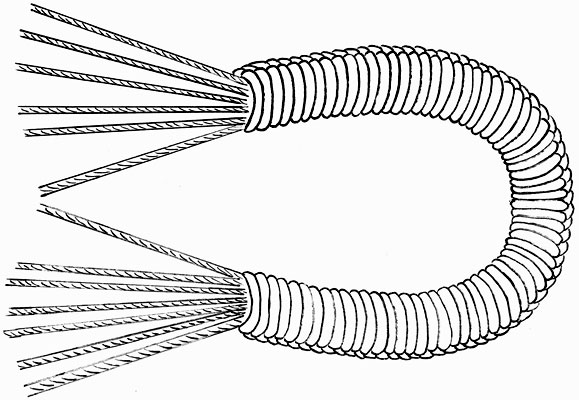

Finally, they use the end of the cord to hold together all the pieces of cord that go around the stick by making successive blanket stitches around it, making a big loop that will also reinforce the hanging area (Figure 6). The same thing has to be then done on the other side of the frame.

Figure 6: The hanging area is reinforced and held together by making successive blanket stitches around the cords.

The only thing left is to take the hammock out of the frame and then it is finished.

A finished hammock. The traditional Waorani hammocks are striped red and white (natural color of the fiber), but many other color combinations can be found nowadays among the Waorani.

REFERENCES

Cabo de Villa, Miguel Ángel., 1999 Los Huaorani en la historia de los pueblos del oriente. Ed. Cicame. Quito, Ecuador.

Cerón M., Carlos Eduardo and Montalvo Ayala, Consuelo., 1998 Etnobotánica de los Huaorani de Quehueiri-Ono, Napo-Ecuador. Ed. Abya-Yala. Quito, Ecuador.

Fuentes C., Bertha., 1997 Huaomoni, Huarani, Cowudi, Una aproximación a los Huaorani en la práctica política multi-étnica ecuatoriana. Ed. Abya-Yala. Quito, Ecuador.

Kidder, Norm., 1996 Making Cordage By Hand. Bulletin of Primitive Technology # 12.

Kritzon, Chuck., 2003 Fishing With Poisons. Bulletin of Primitive Technology #25.

Mondragón, Martha L. and Smith, Randall., 1997 Bete Quiwiguimamo. Salvando el bosque para vivir sano. Centro de Investigación de los Bosques Tropicales - C.I.B.T. Ed. Abya-Yala. Quito, Ecuador.

E-mail your comments to "Miguel de la Iglesia" at migueldelaiglesia@gmail.com

A former version of this article was also published in The Bulleting of Primitive Technology (Fall 2003, #26).

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013