II. Crushing the Clods

The gathered clods were then crushed. Sometimes at Rancho Escondido, where a small band of Southern Diegueño live a little ways down a trail beyond Santa Catarina, Manuela Aguiar's son would do this for her on the bare ground with a metal tool. Any rough rock that fit the hand served to smash the clods on the ground or on a flat stone. A mortar or a grinding stone with a pestle or a mano worked well. Large, unbreakable pieces were picked out and discarded. The resulting crushed material was dried in the sun for a day.

III. Grinding and Sifting

Once dry, on a grinding slab or in a mortar, the crushed clods, including small chunks of mixed clay, mica and other minerals, were completely pulverized, pounded and ground into powder.

Josefina Ochurte's slab was simply a flat rock about 1 foot long and a little under 1 foot wide. It had worn down somewhat unevenly through prolonged use. Her mano was a stream-worn oval boulder that nicely fit her hand. With both hands she pushed it back and forth over the forward edge of a pile of crushed clay on the slab. Little by little finely ground clay began to appear in front of the mano. Coarse clay particles not reduced during this stage and allowed to remain in the clay would lead to shrinkage cracks in fired vessels. For that reason the pulverized clay was thoroughly sifted.

The old way, as demonstrated for Rogers by Southern Diegueño Rosa Lopez, was done on the surface of a parching tray -- a nearly flat basket about 16 inches in diameter. With a few scoops of dry clay powder in the center, the tray was flopped up and down. Large inclusions came to the surface and were picked out. Then the tray was moved to and fro, concentrating coarse particles in the center of the tray, where they were again plucked out. A rotary movement left the fine useful material in the center and carried the remaining coarse bits and pieces to the edge where the flat of the hand pushed them over and away.

Rogers analyzed this method and compared it to a more modern screening. Virtually identical in results, either method increased the clay ratio of Rosa Lopez's raw material, from nearly 16 percent to slightly more than 20 percent. It was now ready to use, complete with its own quartz, feldspar and mica tempering.

Rogers noted that archaeological evidence and early observations showed that the Serrano and the Desert Cahuilla did not add coarse tempering. Sufficient coarse inclusions were already in the residual clays they used. This was true for Rosa Lopez's clay and undoubtedly for the residual clay of the Santa Catarina potters, although some of these added potsherds, ash or even steer manure to the clay to assure that the pots would not crack.

Yuma Indians, who employed sedimentary clays from the Colorado River flood plain and upper terrace, added a scant handful of ground potsherds to a heaping handful of ground clay. This applied to everything but cooking bowls. For cooking ware a handful of decomposed granite, burnt and pulverized, was mixed in with two handfuls of clay.

IV. Adding Water and Kneading

Bunches of yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum) with leaves left on the twigs were soaked in water for twenty-four hours. This liquid, when mixed with the clay, was believed to increase plasticity and to help bond the coils. Rogers referred to a study where tannin (thought to be the substance involved) had this effect and reduced shrinkage as well, while increasing hardness and tensile strength of sun-dried and burned clay. The roasted stems of a cactus (Opuntia occidentalis) were used in the same way. Petra Higuera added a handful of wood ashes to her water.

On a metate or flat rock, the prepared water was poured into the center of a ring of the pulverized clay. Water and clay were mixed and kneaded like dough. It should not be too wet nor too dry. Some pounded it with their fists. Others slapped it between their palms or squeezed and manipulated it. This stage could not be hurried or shrinkage cracks would appear in the pot while drying and certainly when it was fired. Bubbles would cause the pot to explode when fired.

In earlier days, loaves of the prepared clay were wrapped in wet grass and buried in the ground for as long as possible to improve plasticity (through reduction of organic matter). The Yuma would bury the bottom small pats of prepared clay in the wet ground for at least two days in order to ripen. At the time of Rogers' study, Lopez wrapped her clay in wet rags and used it almost at once.

V. Forming the Vessel Base

Josefina Ochurte took a lump about the size of two fists and mashed it like a tortilla on a flat, cloth-covered surface with a smooth, somewhat flattened, large round stone she could just grasp with her fingers. This flat disk of clay was then placed on the bottom of an inverted pot and molded to it. Rogers wrote that Rosa Lopez began with the lump directly on an inverted cooking pot. Such a pot was favored because the wide mouth kept it steady on the ground. Other pots would be used, depending on the vessel intended. Ochurte covered the inverted bowl with an old cloth to prevent sticking. Some potters at Santa Catarina today, and Rosa Lopez in 1928, rubbed wood ashes over the surface for the same effect. When a vessel was unavailable, the potter began a new piece on her flexed knee or on an appropriately shaped basket. Small bowls or jars 4 inches in diameter or less were made from a single or several slabs of clay and were not coiled.

From the lump or disk, a symmetrical base was beaten or tapped out on the mold with a flat wooden paddle about 8 inches long. The blade was about 4 inches square for Lopez, but according to Rogers, older more traditional paddles had a blade twice as long as wide, with the base curved into the handle at the sides instead of forming a right angle.

At Santa Catarina, Josefina Ochurte used the new style paddle, while Margarita Castro still employed the old. Traditionally, paddles were cut and ground from the flat splinter of a fallen tree. The kind of wood mattered little but cottonwood was preferred. Sometimes the scapulae of a deer or mountain sheep served as a paddle.

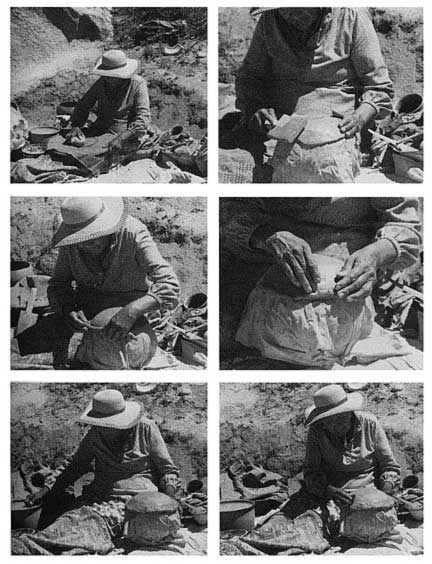

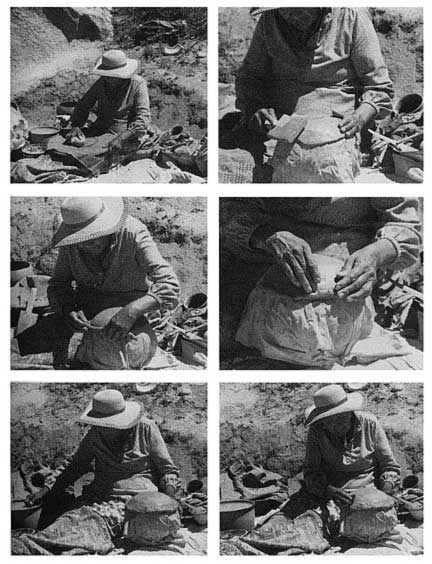

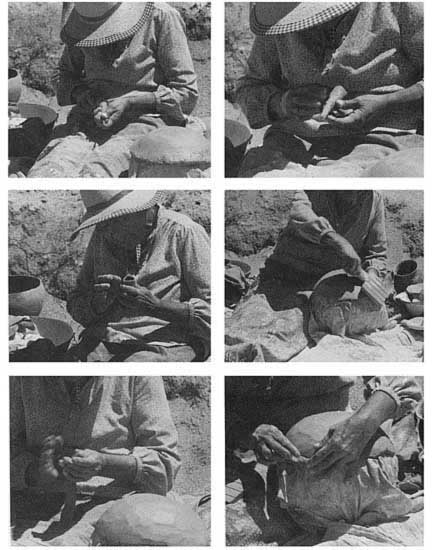

Left to right and down: With large mano Josefina Ochurte flattens ball of clay into tortilla-shaped base for new pot. She paddles it out on cloth-covered bottom of old bowl. A coil is placed and attached with finger tabs. She wets a polished stone and with it smoothes the new coil onto the base.

Before paddling and thinning the new attached coil, she allows some time for drying by working on a clay pipe. She shapes the bowl of the pipe and the stem with her fingers. A smooth stone polishes the exterior of the pipe. She then paddles the coil already attached to the bowl and rolls out a new coil which she places as before.

The article is from the book, entitled "Survival Skills of Native California" (ISBN 0-87905-921-4), by Paul Douglas Campbell. Permission to use the article on the PrimitiveWays website was given by Mr. Campbell. Paul Campbell can be contacted through his publisher, Gibbs Smith, P.O. Box 667, Layton, Utah 84041.

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013