The Ti Plant Called Ki

by Dino Labiste

Over the vast, South Pacific Ocean came the double-hulled canoes,

searching northward into an unknown sea. On these voyagining canoes

were the Children of Tangaroa, Tane, Ti and Rongo. In search of

new land, these Polynesian settlers, called Kanaka Maoli (The

People), came upon a chain of islands. With them they brought

various seeds, tubers and roots to plant in their new homeland,

Hawai'i.

One of the

introduced plants to Hawai'i by the early Polynesians was a tall,

stalk with tightly clustered, green, oval and blade-shaped

leaves. The leaf was about 4 inches wide and varied from 1 to

2 feet long. It was a fast growing woody plant that reached from

3 to 12 feet in height. The plant was Cordyline fruticosa. Known

to the Hawaiians as Ki, it was a ti plant, a member of the lily

family.

One of the

introduced plants to Hawai'i by the early Polynesians was a tall,

stalk with tightly clustered, green, oval and blade-shaped

leaves. The leaf was about 4 inches wide and varied from 1 to

2 feet long. It was a fast growing woody plant that reached from

3 to 12 feet in height. The plant was Cordyline fruticosa. Known

to the Hawaiians as Ki, it was a ti plant, a member of the lily

family.

Ki was considered sacred to the Hawaiian god, Lono, and to

the goddess of the hula, Laka. It was also an emblem of high rank

and divine power. The kahili (ceremonial standard), in its early form, was a Ki stalk

with its clustered foliage of glossy, green leaves at the top.

The leaves were used by the kahuna priests in their ancient religious

ceremonial rituals as protection to ward off evil spirits and

to call in good.

There were many uses for the ti plant in old Hawai'i. The boiled

roots were brewed into a potent liquor known as 'okolehao. The

large, sweet starchy roots were baked and eaten as a dessert.

This versatile plant also had many medicinal uses, either alone

or as a wrapping for other herbs needing to be steamed or boiled.

The ti leaves were wrapped around warm stones to serve as hot

packs, used in poultices and applied to fevered brows. A drink

from boiled green ti leaves were used to aid nerve and muscle

relaxation. Steam from boiled young shoots and leaves made an

effective decongestant. The pleasantly fragrant flowers were also

used for asthma. Besides its use in healing practices, the large

ti leaves became roof thatching, wrappings for cooking food, plates,

cups, fishing lures on hukilau nets, woven into sandals, hula

skirts, leis and rain capes.

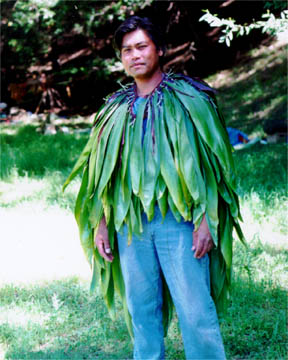

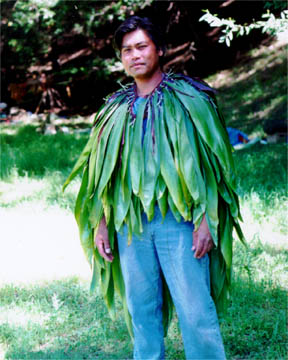

TI LEAF RAIN CAPE

The early Polynesians made a shingled ti leaf rain cape, called

kui la'i, to protect them from the rain and cold. It was

a form of portable ti leaf thatch that was tied to a net foundation

and worn over the shoulders.

To construct a ti leaf rain cape, a fine netting was first

woven. A cord was passed through the neck marginal meshes, knotted

to the meshes at each end, and the cord ends left free for tying.

The traditional netting for the cape in Old Hawai'i was made of

olona (Touchardia latifolia) or

hau (Hibiscus tiliaceus) cordage.

Large ti leaves were gathered.

Large ti leaves were gathered.

The midrib, or bone, from the center of the leaf was removed

from each leaf. The ti leaves were then split in two halves.

The half-leaves were tied to the net mesh, starting

at the bottom of the cape.

The half-leaves were tied to the net mesh, starting

at the bottom of the cape.

Another row of ti half-leaves were added on top of the bottom

row until the layered rows reached the top of the cape.

The thatched ti leaves acted as a wick to drain the water down

the cape. Also the heavy thatching insulated against the cold

winds.

Over time, the constant use, the winds, and the elements shredded

the ti leaves on the cape. The green leaves eventually turned

brown. This did not diminish the practicality of the ti leaf rain

cape.

The ti leaves ability to shed water come from it's semitransparent,

protective surface called the cuticle. The leaf is covered by

a waxy cuticle which keeps water outside and restricts evaporative

water loss from the plant.

The many parallel veins, which provide strength, is another reason

why the ti leaf is a good plant resource. Leaf veins are vascular

bundles and have a fibrous bundle sheath. Vascular bundles are

composed of xylem (a tissue having pipelines that conduct water

and dissolved mineral ions), phloem (a tissue having pipelines

which distribute dissolved sugars and other photosynthetic products),

and fibers which support and protect the xylem and phloem. Fibers

and vascular bundles in leaves are called fibrovascular bundles.

The fibers and the xylem in fibrovascular bundles make ti leaves

strong, thus the many uses of this versatile plant.

E-mail your comments to "Dino Labiste" at KahikoArts@yahoo.com

PrimitiveWays

Home Page

We hope the information on the PrimitiveWays website is both instructional and enjoyable. Understand that no warranty or guarantee is included. We expect adults to act responsibly and children to be supervised by a responsible adult. If you use the information on this site to create your own projects or if you try techniques described on PrimitiveWays, behave in accordance with applicable laws, and think about the sustainability of natural resources. Using tools or techniques described on PrimitiveWays can be dangerous with exposure to heavy, sharp or pointed objects, fire, stone tools and hazards present in outdoor settings. Without proper care and caution, or if done incorrectly, there is a risk of property damage, personal injury or even death. So, be advised: Anyone using any information provided on the PrimitiveWays website assumes responsibility for using proper care and caution to protect property, the life, health and safety of himself or herself and all others. He or she expressly assumes all risk of harm or damage to all persons or property proximately caused by the use of this information.

© PrimitiveWays 2013

One of the

introduced plants to Hawai'i by the early Polynesians was a tall,

stalk with tightly clustered, green, oval and blade-shaped

leaves. The leaf was about 4 inches wide and varied from 1 to

2 feet long. It was a fast growing woody plant that reached from

3 to 12 feet in height. The plant was Cordyline fruticosa. Known

to the Hawaiians as Ki, it was a ti plant, a member of the lily

family.

One of the

introduced plants to Hawai'i by the early Polynesians was a tall,

stalk with tightly clustered, green, oval and blade-shaped

leaves. The leaf was about 4 inches wide and varied from 1 to

2 feet long. It was a fast growing woody plant that reached from

3 to 12 feet in height. The plant was Cordyline fruticosa. Known

to the Hawaiians as Ki, it was a ti plant, a member of the lily

family.